Portfolio Review – Q3 2021 – Issue 12

This is the latest One Four Nine Portfolio Management (OFNPM) portfolio review providing investors and advisers with an easy to digest overview of what’s happening in the markets globally, alongside comparisons of OFNPM’s portfolio performance each quarter and throughout the year.

Chief Investment Officer’s comments

Inflation continues to be the dominant theme in markets, as it has been all year. Headline yearly rates of change in the consumers price index continue to be significantly higher than central bank targets in most developed economies. In the UK CPI is running at 3.1% and has been above the Bank of England’s target of 2.0% since May. In the US it is a similar story, where CPI is running at 5.4%, well above the Fed’s target of 2.0%. It was last below this in February. In Europe too inflation rates have been increasing with Germany and Spain recording rates just above 4.0%, while France and Italy have seen more modest rates at 2.1% and 2.6%. Finally, Japan, which has had almost no inflation for over 25 years, has bucked the trend of global price increases with yearly CPI running at just 0.2%.

So why are we seeing increased rates of inflation, will it last, why does it matter and finally what will the effects on markets be? I’ll attempt to answer these questions but not in the order posed.

Firstly, why does higher inflation matter?

Inflation has a nasty habit of deflating the value of your investments. The higher inflation is, the more quickly the purchasing power of your assets deflates. If, for instance, inflation is running at 2.0% p.a. the purchasing power of £100 pounds today in ten years’ time will be £82. If inflation however is running at double that rate (i.e. 4.0% p.a.) the purchasing power of £100 in ten years’ time is now only £68. Inflation has eroded the value of your assets by 32.0%! At 8.0% p.a. the value falls further to £46 over ten years. This matters particularly for those with cash and fixed incomes, hence why we invest, as historically financial assets have generally provided a return in excess of inflation, providing protection from the corrosive properties of inflation. The exception has been cash since the Great Financial Crisis (GFC), which has provided a negative real return.

For the last thirty years, since the advent of inflation targeting by central banks, we have lived in a low inflationary environment. It could be inferred (mistakenly) that it has been explicit targeting that has resulted in this low inflationary world, but there have been larger forces at play. Globalisation has been the biggest factor in keeping inflation low as downward pressure has been placed on domestic wages and the developed world has imported productivity gains from developing markets, with their low wages. In the developed sphere aging demographics and slowing population growth has meant downward pressures on aggregate demand. And finally, technology and innovation has been inherently deflationary.

What has changed in the past year?

So, what has changed in the past year to see inflation rates reach near highs of the past thirty years. There is a myriad of reasons. Firstly, we are experiencing base effects from the loss of aggregate demand in the early stages of the pandemic. Last year we saw very low levels of inflation, and in some instances deflation. With the reopening of economies and a surge in aggregate demand we are experiencing companies trying to recoup losses from last year, and consumers seem happy to pay the price. Secondly, we have seen a rebound in the input prices of commodities, especially energy, linked to this increase in demand. This has started to feed into higher inflation. Thirdly we have seen some rebound in wage levels, which had been repressed during 2020, coupled with lower than expected unemployment. In certain sectors we have had labour shortages which has helped to drive-up short-term wages.

However, the single biggest factor has been an unprecedented short-term expansion of government deficits to help plug the demand driven hole in economies from shutdowns. The support governments have given and are continuing to give their economies has helped fuel inflation, not least because the borrowing has been funded by central bank balance sheet expansion, not by conventional borrowing. Money printing by central banks to stabilise economies, generate inflation and deflate debt was the playbook after the GFC, but higher inflation never eventuated as the money printing resulted simply in asset swaps between central banks and commercial banks, which shored up balance sheets and never made its way into the real economy. It caused a repression of interest rates, and inflation in financial assets, but stopped there.

Is this higher rate of inflation set to continue?

The big question facing us is, is this higher rate of inflation set to continue? To a certain extent we should see the headline rate remain high until at least the summer of 2022. At this point the base effects of higher prices now will start to work its way out of the data if month on month changes revert towards more normal levels. I see no reason why in the long-term this should not be the case. The headwinds of the last 30 years seem set to continue with demographics, globalisation and technological advances all set to be deflationary, offsetting any short-term inflationary factors such as energy prices and wage increases.

There are fundamental risks to this view. If governments continue to run higher than expected deficits then unchecked government spending, not for long-term investment with productivity gains, will be a long-term inflationary risk. The fragility of global supply chains, exposed during the pandemic (and to a certain extent Brexit in the UK) may lead to companies looking to make these supply chains more local, which with higher wages in developed countries, will be moderately inflationary. Also, China is facing its own demographic crisis as the one-child policy of the 1980s and its aging population comes home to roost. This reduced labour force will start to demand higher wages, which implies that the exporting of Chinese deflation to the west will reverse to become an export of Chinese inflation. Finally, the increasing need to decarbonise society to reduce global warming and environmental damage will need an almighty effort from government and companies alike. The spending to achieve this will be huge and we should not underestimate the inflationary effects of this increased spending in the medium-term.

What of the effects on markets?

Higher unexpected inflation is bad for bond markets as participants look towards higher rates from central banks in an attempt to rein in inflation. Gilts over the quarter fell 1.9% while investment grade sterling credit fell 1.0%. The risk in the short-term to bond markets is clearly on the downside. In fact, we saw two central banks, New Zealand and Poland, raise rates over the fear of higher-than-expected inflation. Both the BoE and the Fed have intimated that their interest rate policies are being watched closely. However, the weight of debt now carried by governments, means that central banks have little room to manoeuvre on interest rates. They are well aware that if they move too aggressively on rate increases, they may well cause a financial crisis, which neither they nor governments could extricate us from. Better to allow a bit more inflation, hope for technology driven productivity alongside economic growth, and watch the debt deflate away.

The effects on equity markets are less certain. Over the past quarter we have continued to see positive performance from equity markets. In local currency terms UK equities gained 2.2%, US equities 0.6%, European equities 0.4% and Japanese equities 5.3%. Only Asia Pacific (-6.2%) and Emerging Markets (-5.8%) delivered negative returns. Slightly higher inflation may allow companies with pricing power to generate higher earnings, but only if they can control underlying costs or somehow improve productivity. In the absence of these factors higher than expected inflation should result in a higher weighted average cost of capital, which will deflate the present value of future cashflows, resulting in lower equity valuations.

Portfolio performance

Your portfolios generated positive performance over the quarter. The table below shows returns for Active and Passive portfolios, alongside the returns of their respective inflation benchmarks and for comparison purposes their appropriate private client ARC index.

| Active | Passive | Inflation Benchmark | ARC Index | |

| Defensive | 0.69% | 0.52% | 1.17% | |

| Cautious | 0.84% | 0.50% | 1.42% | -0.21% |

| Balanced | 1.30% | 0.78% | 1.66% | 0.28% |

| Growth | 1.61% | 1.03% | 1.90% | 0.66% |

| Adventurous | 1.96% | 1.28% | 2.13% | 1.05% |

Our active portfolios outperformed both the passive portfolios and the ARC indices over the quarter. Our fund selection added to your returns over the quarter as our active portfolios outperformed their passive equivalents. Moreover, our passive portfolios outperformed the ARC indices which implies some extra return from our medium-term tactical asset allocation. This was higher the lower down the risk spectrum we go, indicating that the primary driver was our low duration positioning in the bond markets relative to ARC managers.

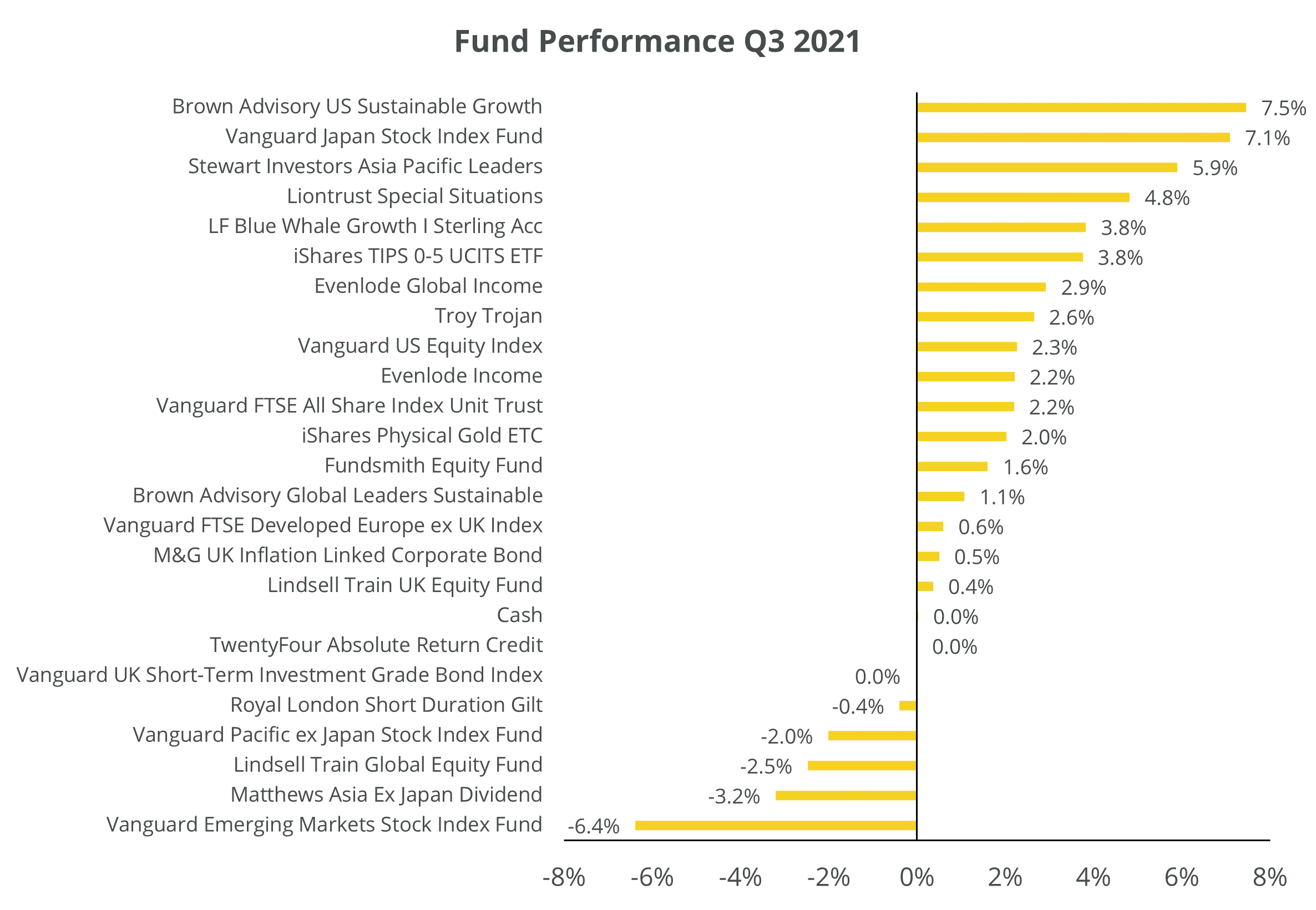

The chart below shows the returns of funds within the portfolios for the quarter.

The five top performers in the active portfolios were:

- Brown Advisory US Sustainable Growth (+7.5%)

- Stewart Asia Pacific Sustainable Leaders (+5.9%)

- Liontrust Special Situations (+4.8%)

- Blue Whale Growth (+3.8%)

- Evenlode Global Income (+2.9%)

Of our 11 active equity funds seven outperformed their index, while four underperformed but only two funds realised negative returns. The active equity funds returned 2.03% over the quarter while their passive equivalents retuned 1.35%.

Our bond funds provided good protection from rising yields and falling returns in the bond market. Our short duration gilt fund fell 0.40%, but the wider gilt market fell 1.93%. Our credit funds were either flat (Twenty-Four ARC and Vanguard UK Short-term Investment Grade) or produced positive returns (M&G UK Inflation Linked Corporate Bond Fund). The Sterling corporate bond market fell 0.99% over the quarter.

Portfolio outlook

We made no changes to the portfolios over the quarter. Overall, our long-term outlook remains unchanged.

- The world is in a secular disinflationary environment. Some short-term inflation is expected due to demand/supply imbalances, but this should dissipate in the second half of 2022

- Equilibrium rates will be at far lower levels than they were pre GFC for much longer. Covid-19 has compounded this. Real rates will remain negative

- We must adjust to permanently lower risk premia. We get paid less for taking on the same risk

- Monetary policy is now ineffective as a tool to combat future recessions

- Fiscal policy will have to take up the slack with ever expanding Government balance sheets

- Fiscal policy will remain loose for much longer to combat the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic

- Global demand and growth will remain weak while Covid-19 remains a risk to global health

- Outlook for fixed income is poor with large amounts of negative yields. Trade is on a greater fool theory

- Equities still provide resilience but only those companies with strong balance sheets, good cash flows, strong brands and barriers to entry will provide long-term value

Find out how One Four Nine Portfolio Management invest here.

Dr Bevan Blair,

Chief Investment Officer,

One Four Nine Portfolio Management

London, Thursday 28 October 2021.

All investment views are presented for information only and are not a personal recommendation to buy or sell. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future returns, investing involves risk and the value of investments, and the income from them, may fall as well as rise and are not guaranteed. Investors may not get back the original amount invested.

All data is at 30 September 2021. One Four Nine Models are benchmarked against UK CPI and any other benchmark has been displayed for comparative purposes only and is not a benchmark for the Models. Performance figures are net of underlying fund fees and include One Four Nine Portfolio Management’s Management Fee of 0.24% (including VAT). All model portfolio performance data is sourced from One Four Nine Portfolio Management. All other data is from Bloomberg and Morningstar.

This service is intended for use by investment professionals only. This document does not constitute personal advice. If you are in doubt as to the suitability of an investment, please contact your adviser.

One Four Nine Group Limited Registered in England No: 11866793. One Four Nine Portfolio Management Limited is registered in England No: 11871594 and is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) FRN: 931954. One Four Nine® is a registered trademark.